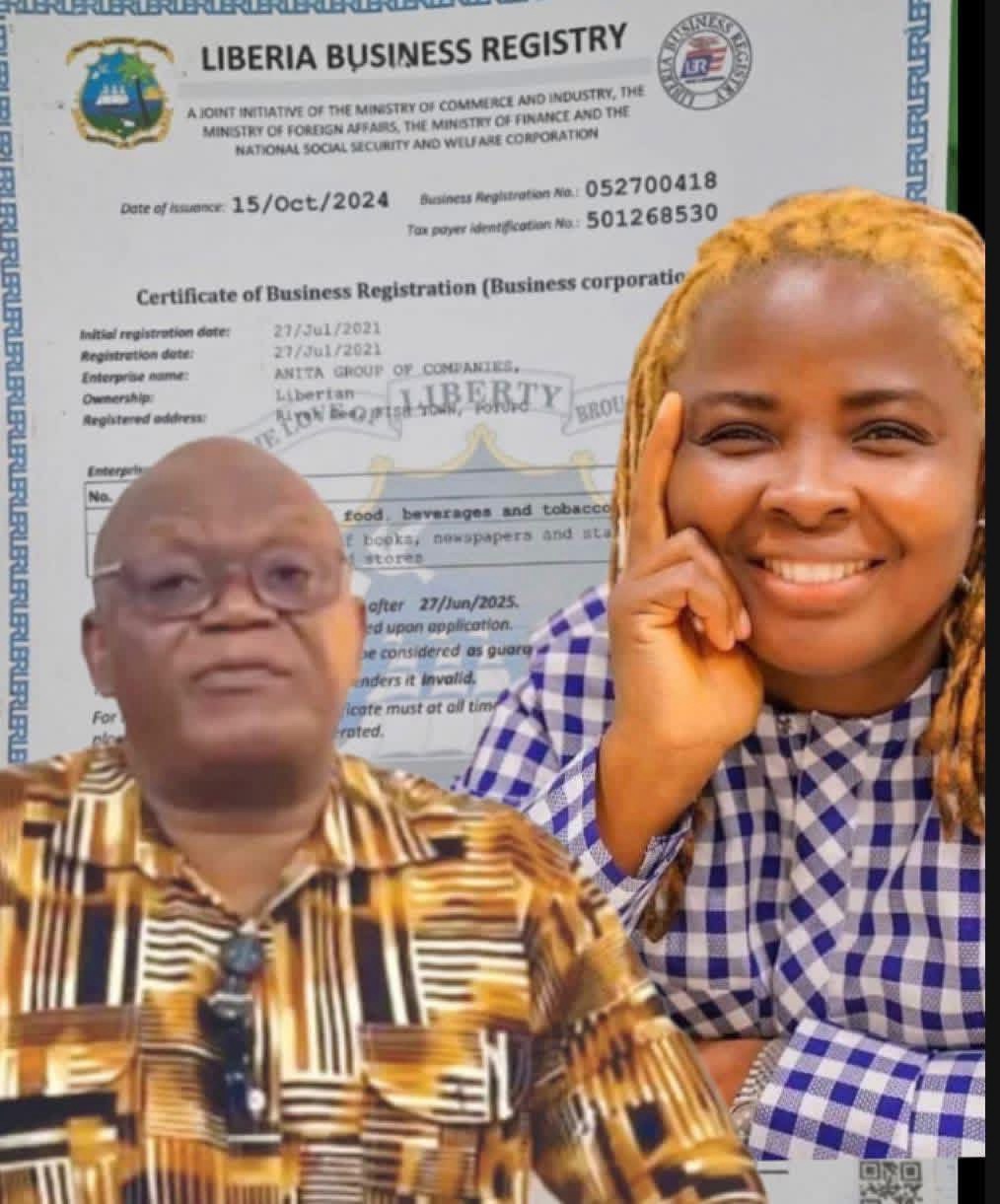

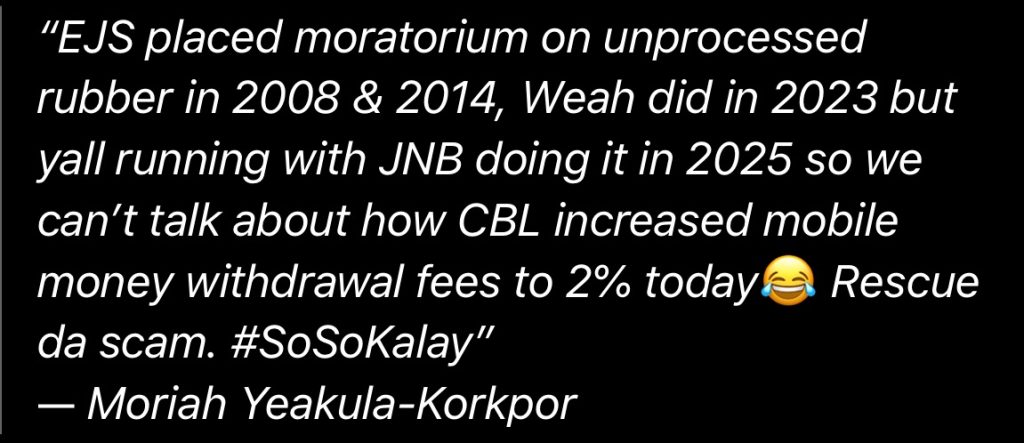

Monrovia, Liberia – A recent social media post has sparked debate over the implementation of export restrictions on unprocessed rubber and the Central Bank of Liberia’s (CBL) latest move to raise mobile money withdrawal fees to 2%.

The post by political commentator Moriah Yeakula-Korkpor highlights the policy pattern of successive Liberian governments regarding rubber exports while raising concern over a recent CBL decision impacting mobile money users.

Rubber Export Moratoriums: A Historical Look

Former President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf (EJS) introduced a moratorium on the export of unprocessed rubber in 2008, aimed at encouraging local value addition and industrial growth. The measure was revisited and reintroduced in 2014, again with the goal of boosting domestic processing to create jobs and retain more economic benefits within Liberia.

Under President George Weah, a similar moratorium was declared in 2023, continuing the trend of restricting raw rubber exports to support local manufacturing efforts. Now, the current administration under President Joseph N. Boakai (JNB) has reportedly extended or reintroduced the policy in 2025.

The criticism raised in the post suggests that this continuity of policy is being overly politicized in favor of JNB while ignoring its roots under past administrations.

CBL’s Controversial 2% Mobile Money Fee

Simultaneously, the Central Bank of Liberia has introduced a 2% fee on mobile money withdrawals, sparking public outcry. The increase, announced in August 2025, affects thousands of low-income Liberians who rely on mobile money platforms for daily transactions.

Critics argue that the fee is regressive, disproportionately impacting the poor, especially in rural areas where mobile money is more accessible than traditional banking services.

The concern expressed by Yeakula-Korkpor suggests that the public discourse has been distracted by recycled economic policies like the rubber export moratorium, while new fiscal burdens such as the CBL’s fee hike receive insufficient scrutiny.

Public Reactions and Implications

Liberians on both sides of the political spectrum have voiced frustration over rising costs and perceived government insensitivity to economic hardship. Civil society groups have begun calling for greater transparency in monetary policy decisions, especially those that affect vulnerable populations.

Meanwhile, defenders of the mobile money fee argue that it may help the government generate revenue for infrastructure and regulatory improvements in the financial sector.

Conclusion

While moratoriums on unprocessed rubber exports are not new in Liberia, the timing and framing of their implementation often reflect deeper political narratives. As the CBL’s mobile money policy change unfolds, it is essential for stakeholders to ensure that critical economic issues are not overshadowed by partisan distractions. Clear communication, public engagement, and equitable policymaking remain key to navigating Liberia’s complex financial future